Lula's Return

- Giancarlo Da-Ré

- Mar 10, 2023

- 3 min read

Updated: Sep 15, 2023

Brazil will need leadership to push through mitigation and adaptation challenges

Last weekend I had the privilege of competing in São Paulo at the Global Public Policy Network’s annual case competition. Like many of my competitors from New York, London, and Tokyo (among others), it was my first time visiting Brazil. The theme of the conference was vague: policy challenges in an ever-more divided world. But there was something else on my mind that weekend.

A week before my visit, heavy storms caused flooding and landslides on the South-East state of São Paulo (if you didn’t know, São Paulo is both a city and a state). At least 54 lives were lost.

High-sloping streets and poor adaptation infrastructure is a bad combination for heavy storms. While wealthier communities can purchase homes in safer areas, poorer communities (especially the favelas) are stuck living in unsafe areas. The professors I spoke with call it the zip-code lottery. Tragically, this is just the latest consequence of bad adaptation infrastructure in the region.

When people think of Brazil and climate change, the mental connection often lands on the 2.6 million square mile Amazon rainforest—the world’s largest intact forest. Last month’s devastating events in São Paulo show, however, that while Brazil has an outsized global impact on carbon emissions mitigation, it also needs serious advancements to its adaptation infrastructure. The truth is, we need to be able to walk and chew gum at the same time.

Far from Brazil’s 2009 commitment to reduce the Amazonian deforestation rate by 80% in 2020, the 2020 deforestation rate was 182% higher than the established target.

There are several reasons for this failure, beginning with controversial changes to the Brazilian Forest Code in 2012, then followed by a disregard for related climate change policies, poor deforestation enforcement actions, and laws that regularized illegal public land grabs.

These setbacks can make the fight against climate change feel like a Sisyphean task. Just as progress is made, it seems we're destined to roll back down the hill. But amidst the disheartening data, there are reasons to feel hopeful.

Since Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva took over as President this year, his government has been working quickly to remake Brazil. Less than a year since President Jair Bolsonaro’s attempt to fast-track what environmentalists dubbed the “death package” through Congress, President Lula da Silva’s government has already consulted with Chile, Mexico, and Germany on a new Green Bond Framework.

This builds off work from the Brazil Climate Finance Project between the World Bank and Banco do Brasil, which just recently provided Brazil with USD$500 million in sustainability-linked finance. This, in turn, is expected to mobilize up to USD$1.4 billion in private capital through scale-up financing.

(While significant, this is still less than the anticipated USD$10 billion per year needed to hit Brazil’s climate targets.)

Last month was also marked by a pivotal meeting in Washington between the two heads of state, where Presidents Biden and Lula da Silva reaffirmed the importance of tackling climate change and discussed ways to strengthen their countries' joint efforts.

One of the big takeaways from the meeting was instruction for the United States-Brazil Climate Change Working Group (CCWG) to reconvene as early as possible to begin advancing areas of cooperation. The CCWG, created by the Joint Initiative on Climate Change, will work to fight deforestation and degradation, enhance the bioeconomy, bolster clean energy deployment, strengthen adaptation actions, and promote low carbon agriculture practices. If executed properly, these initiatives can secure a triple win—creating more sustainable jobs, protecting natural resources, and reducing carbon emissions.

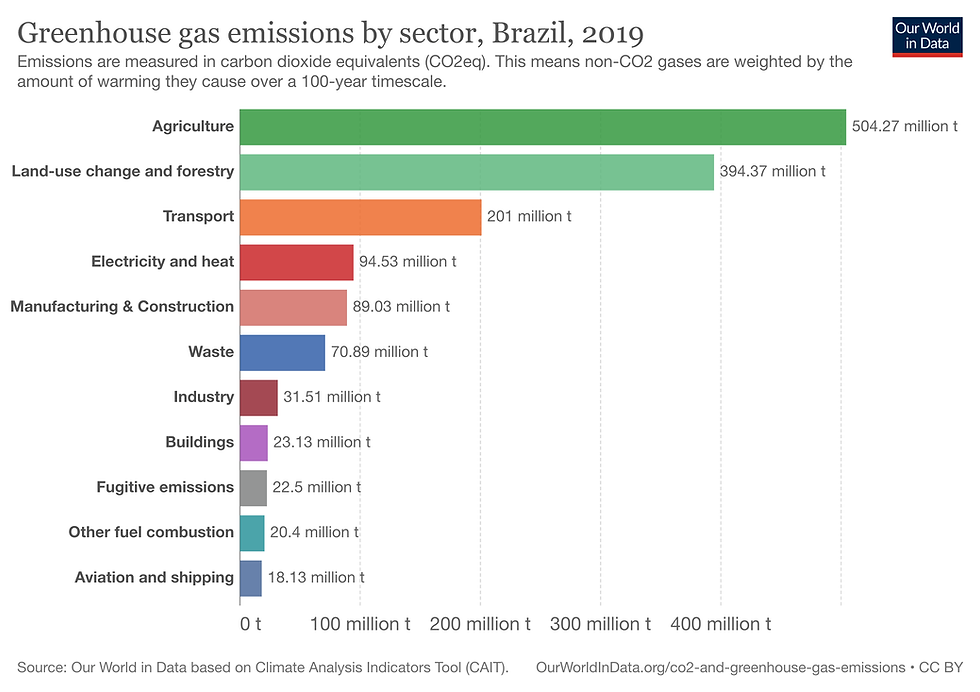

Reducing emissions from Brazil’s agricultural and forestry sectors will be particularly critical in hitting their 2050 net-zero target. As shown below, these two sectors make up the lion’s share of overall emissions.

Another key takeaway from the Washington meeting was a joint commitment to fight deforestation and degradation. This included a pledge by President Biden to work with Congress on funds for rainforest conservation programs, including an initial USD$50 million donation to the Amazon Fund.

(Though President Bolsonaro suspended the USD$1.2 billion Amazon Fund in 2019, President Lula da Silva revived it on his first day of office in 2023.)

I’ll note that this initial donation by the United States appears to be missing a few zeros... During his presidential campaign, President Biden promised to mobilize USD$20 billion towards the Amazon. I’ve written before about the challenges to increased climate finance, and in fairness to President Biden, there is increased political resistance with Republicans in control of the House and the fact that the 2024 campaign season has already begun. Like his counterpart in Brazil, President Biden has a tough hill to climb if he is to fulfill his promises.

But while these are positive steps forward, they shouldn’t cloud the fact that Brazil needs adaptation resources to help itself just as much as the world needs help from Brazil’s carbon sink.

Comments